A yeast library is a collection of genes derived from a specific organism or sample, cloned into yeast-compatible vectors. It enables systematic screening of protein interactions without testing candidates one by one.

As life science research continues to advance, analyzing protein–protein interactions has become a routine and essential approach for exploring cellular pathways and biological mechanisms. In many research projects, however, the primary challenge is not how to test protein interactions, but how to identify meaningful interaction partners in an efficient and unbiased way.

To understand why building a yeast library matters, it is useful to consider a common experimental scenario.

Imagine a graduate student beginning a research project in plant biology. Through genetic analysis, the student discovers that a mutation in gene A affects early-stage rice growth under specific temperature conditions. Naturally, the next question is which proteins interact with the protein encoded by gene A.

Using bioinformatic prediction tools and literature searches, the student identifies several candidate interaction partners—proteins B, C, D, E, and F. To experimentally validate these candidates, the student employs a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system.

This process requires constructing a BD (bait) vector for gene A, along with individual AD (prey) vectors for each candidate protein. After testing these interactions one by one, only protein D shows a detectable interaction.

At this point, a critical question remains unanswered:

Is protein D the only interacting partner, or simply the only one that happened to be tested?

This scenario reflects a broader limitation of traditional interaction validation strategies:

Candidate interaction partners are chosen based on predictions or prior publications

Each experiment tests interactions in a one-to-one manner

Every additional candidate requires new cloning, transformation, and screening steps

Bioinformatic predictions are inherently incomplete and context-dependent

As a result, interaction discovery becomes a process of educated guessing. Important but unexpected interaction partners may never be examined simply because they were not predicted in advance.

This approach is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and often inefficient—especially when the goal is discovery rather than confirmation.

A yeast library fundamentally shifts protein interaction studies from a candidate-driven validation model to a systematic screening model.

A yeast library can be understood as a comprehensive collection of expressed genes from a given organism, cloned in advance into AD vectors. Instead of constructing AD plasmids one by one, researchers can screen a single bait protein against a large population of potential interaction partners in a single experiment.

In practice, this means:

Only the bait (BD) construct needs to be generated

The bait is screened directly against the yeast library

Interaction candidates are identified through large-scale screening rather than sequential guessing

Rather than asking “Which proteins should I test?”, the experiment becomes “Which proteins in this organism are capable of interacting with my protein of interest under this screening system?”

Once the decision is made to adopt a systematic screening strategy, a practical question follows: what materials are needed to construct a custom yeast library?

In practice, a wide range of biological materials can be used for yeast library construction, particularly in biomedical research. These include:

pathological tissues

tumor tissues and matched adjacent samples

disease-relevant primary cells or cultured cell lines

For most projects, yeast library construction typically requires approximately 2 g of tissue or ~10⁷ cells, depending on sample type and library design. RNA extracted from these materials serves as the foundation for downstream cDNA library construction.

Building a yeast library is not an end in itself. Its value lies in the range and depth of interaction data it enables researchers to generate—data that are difficult or inefficient to obtain using one-by-one validation approaches.

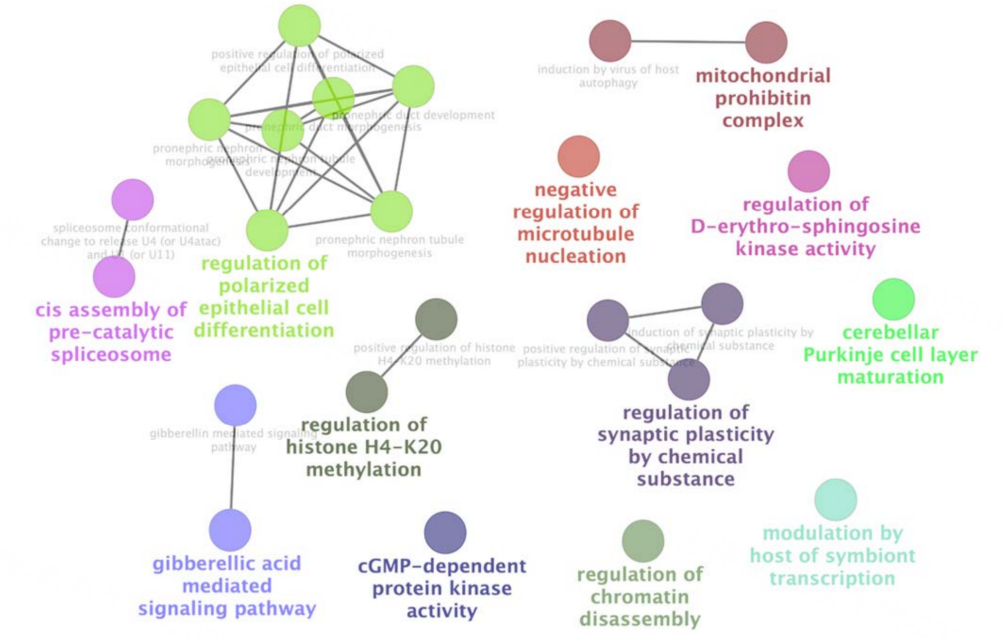

Using a coding sequence (CDS) as bait, a custom yeast library enables large-scale protein–protein interaction screening. This supports:

construction of protein interaction networks

identification of disease-associated interaction partners

discovery of potential drug targets or biomarker candidates

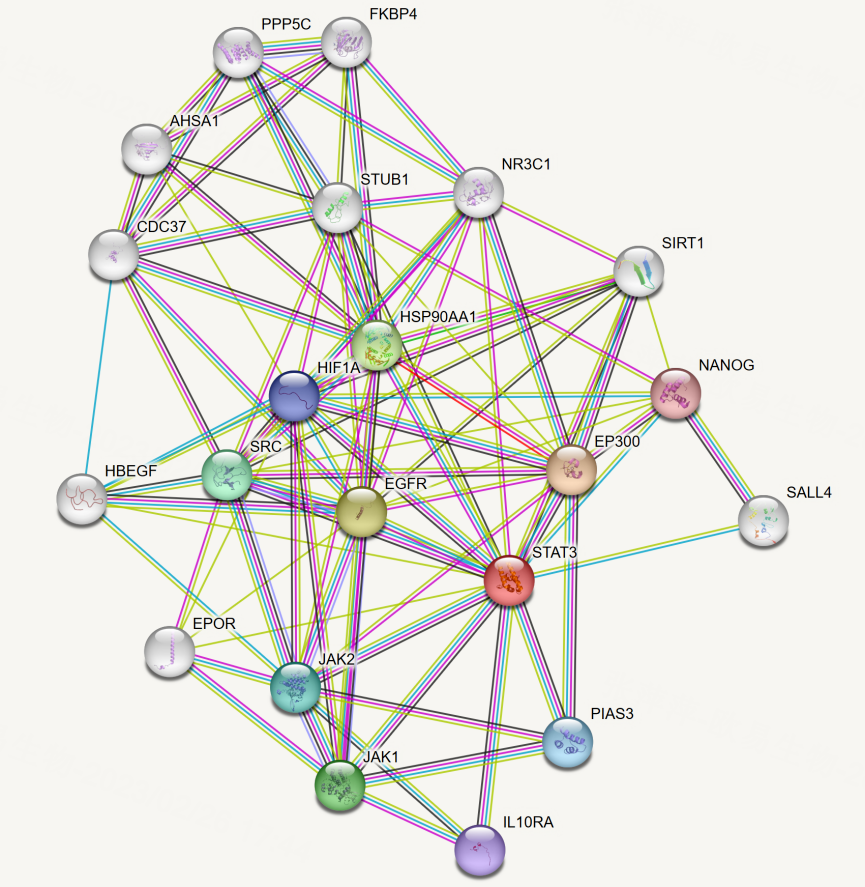

High-throughput yeast library screening has been successfully applied to characterize complex interactomes in human tissues, including disease-relevant contexts, such as the pVHL interactome in human testis.

Yeast libraries are not limited to protein–protein interaction studies. They can also be applied to protein–DNA interaction screening, such as yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays.

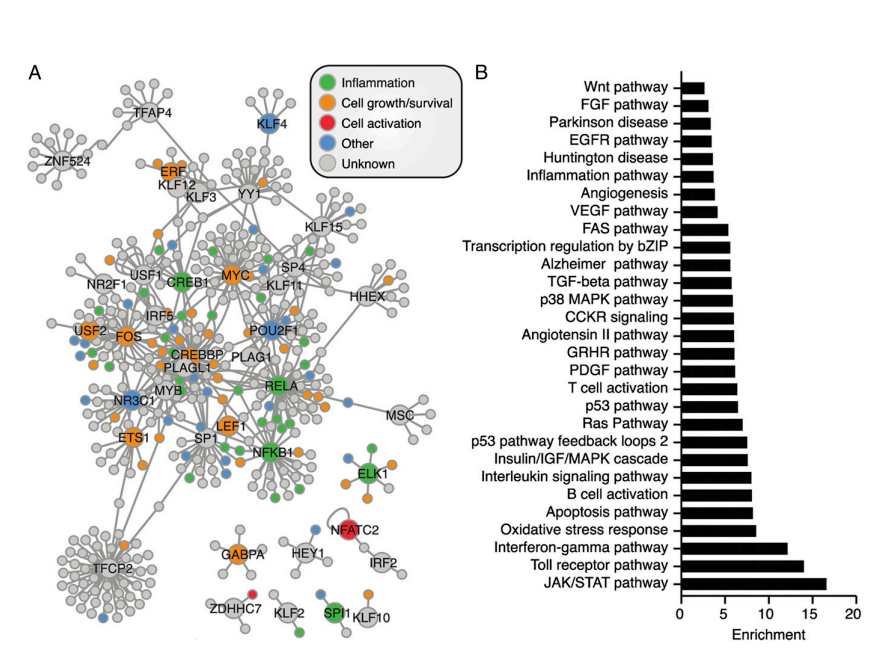

By using promoter or regulatory DNA elements as bait, researchers can identify upstream regulatory proteins—including transcription factors, chromatin-associated proteins, and other DNA-binding factors—thereby uncovering transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. This approach has been used to map regulatory networks controlling viral gene expression, including HIV-1 and HIV-2.

Interaction candidates identified through yeast library screening can be compared with existing PPI databases, such as STRING and BioGRID, to highlight:

interactions absent from current databases

tissue- or condition-specific interaction events

potential gaps or biases in public datasets

In this way, custom yeast libraries provide an experimental route to extend and refine existing interaction knowledge, rather than simply reproducing known results.

Proteomics-based approaches such as AP-MS, pull-down assays, and IP-MS are powerful but often generate extensive candidate lists that require substantial downstream filtering.

Yeast library screening offers a focused discovery layer, helping researchers narrow down interaction candidates before committing extensive resources to validation.

Antibody-dependent approaches, such as Co-IP, are sensitive to antibody quality and performance. In practice, unsuitable antibodies can lead to failed experiments and unnecessary expenditure.

By identifying candidate interactions through yeast library screening first, researchers can reduce reliance on trial-and-error antibody testing and improve overall experimental efficiency.

Once constructed and quality-controlled, a yeast library is not a single-use reagent. The same library can be screened repeatedly against different bait proteins.

This reusability allows interaction screening to scale with research needs—one library can support essentially unlimited rounds of screening, making it a long-term research asset rather than a one-off experimental tool.

Constructing a high-quality yeast library is not a routine cloning task. Library complexity, insert representation, RNA quality, and quality control at each step all directly influence the reliability and interpretability of downstream interaction screening results.

At Omics Empower, yeast library construction is a long-established core capability, supported by extensive project experience and validated research outcomes.

10+ years of yeast library construction experience, supporting 140+ peer-reviewed publications, including Science and Cell cover articles

Gateway- and SMART-based library construction, adaptable to different sample input amounts

Extensive RNA extraction expertise with multiple optimized workflows to ensure high-quality RNA

12 quality control checkpoints throughout library construction to ensure library integrity and reproducibility

Custom yeast library construction supporting Y2H and Y1H interaction screening.

Schedule a complimentary project consultation today.

Reference

1. Falconieri A, Minervini G, Quaglia F, Sartori G, Tosatto SCE. Characterization of the pVHL interactome in human testis using high-throughput library screening. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Feb 17;14(4):1009. doi:10.3390/cancers14041009.

2. Pedro KD, Agosto LM, Sewell JA, Eberenz KA, He X, Fuxman Bass JI, Henderson AJ. A functional screen identifies transcriptional networks that regulate HIV-1 and HIV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Mar 16;118(11):e2012835118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2012835118.

A yeast library is a collection of genes derived from a specific organism or sample, cloned into yeast-compatible vectors. It enables systematic screening of protein interactions without testing candidates one by one.

Germany: Arnold-Graffi-Haus / D85 Robert-Rössle-Straße 10 13125 Berlin

United States: (CA) 2 Goddard, Irvine, CA 92618 • (IL) 8255 Lemont Rd, #1, Darien, IL 60561

Hong Kong: Room 618, Building 6, Phase One, Hong Kong Science Park, No. 6 Science Park West Avenue, Pak Shek Kok, New Territories, Hong Kong

Germany: Arnold-Graffi-Haus / D85 Robert-Rössle-Straße 10 13125 Berlin

United States: (CA) 2 Goddard, Irvine, CA 92618 • (IL) 8255 Lemont Rd, #1, Darien, IL 60561

Hong Kong: Room 618, Building 6, Phase One, Hong Kong Science Park, No. 6 Science Park West Avenue, Pak Shek Kok, New Territories, Hong Kong