This approach is useful when matched single-cell data are unavailable, poorly matched, or when researchers want to explore spatial organization before conducting additional single-cell sequencing experiments.

Spatial transcriptomics technologies enable researchers to measure gene expression while preserving spatial context, and have become widely used in cancer biology, neuroscience, and developmental studies. For many commonly used spot-based platforms, however, each spatial spot typically aggregates transcripts from multiple cells. This creates a core analytical challenge: how to infer cell-type composition and spatial organization from mixed spot-level signals.

Figure 1. Mixed transcriptional signals in spatial transcriptomics.

A common solution is cell-type deconvolution, where cell-type signatures derived from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) are used as reference profiles to estimate proportions in each spatial spot. In practice, matched or well-aligned single-cell references are frequently unavailable, which can limit the reliability of reference-based approaches.

This leads to a practical question in many spatial transcriptomics projects:

Can spatial transcriptomics be analyzed in a principled way when no suitable single-cell reference data exist?

Reference-based deconvolution is conceptually straightforward, but it depends on assumptions that are often difficult to meet:

No matched single-cell dataset from the same tissue, condition, or experimental context

Public scRNA-seq references are not truly comparable, due to biological differences and technical batch effects

Cell states present in spatial tissue may not be represented in the reference dataset

When the reference is poorly matched, the downstream estimates can become unstable or difficult to interpret biologically (e.g., ambiguous cell-type calls, inconsistent spatial patterns). This is not a failure of deconvolution as a concept; it is a data alignment problem that many real-world studies face.

To address this limitation, reference-free deconvolution approaches have been developed. One such method is SURF (Self-sUpervised, Reference-Free deconvolution), which is designed specifically for spot-based spatial transcriptomics data.

Rather than relying on scRNA-seq reference profiles, SURF infers latent cellular components directly from the spatial transcriptomics dataset itself. The method uses only the spatial gene expression matrix together with spot-level spatial coordinates, allowing cell-type-like structures to be learned without prior cell-type definitions.

This design makes reference-free deconvolution particularly relevant for studies in which single-cell data are unavailable, incomplete, or unsuitable as references.

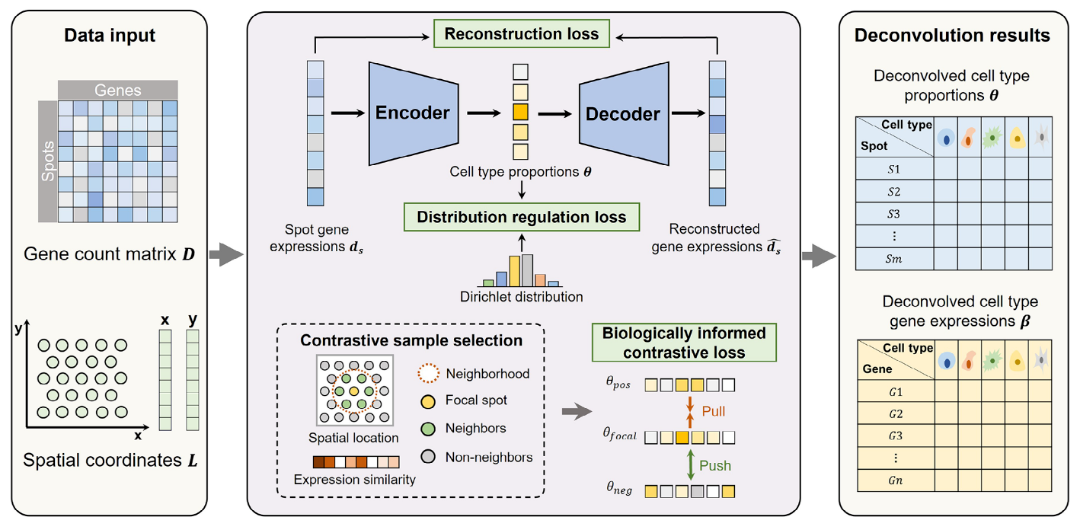

SURF is built on a self-supervised deep learning framework tailored to spatial transcriptomics analysis. At a high level, the method combines three key elements.

First, SURF uses an autoencoder-based architecture to model complex, non-linear gene expression patterns in high-dimensional spatial data. This allows the model to learn compact representations of expression variability across spots.

Second, the method incorporates regularization on spot-level mixture proportions, encouraging biologically plausible distributions of latent components across spatial locations.

Third, spatial relationships between neighboring spots are explicitly incorporated during model training. By considering both expression similarity and spatial proximity, SURF learns representations that reflect tissue organization rather than expression patterns alone.

The output of SURF consists of latent components and their estimated proportions across spatial spots. These components represent putative cell populations or cell states and require downstream biological annotation using marker genes, pathway enrichment, and domain expertise.

Figure 2. Overview of the SURF reference-free deconvolution framework

SURF has been evaluated on spatial transcriptomics datasets generated using different platforms and across diverse biological systems. These benchmarks demonstrate that reference-free deconvolution can recover meaningful spatial structure directly from spatial transcriptomics data.

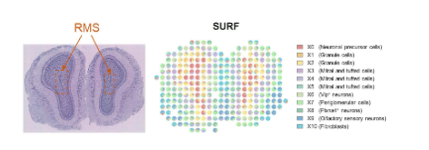

In a mouse olfactory bulb dataset generated using the 10x Genomics Visium v1 platform, SURF identified 11 latent cellular components. One component (X0) was spatially enriched in the rostral migratory stream (RMS), a region known to contain migrating neural progenitor cells.

This spatial pattern was supported by the enrichment of neurogenesis-related marker genes such as Sox11, as well as pathways associated with synaptic plasticity and neuronal development.

Figure 3. Mouse olfactory bulb spatial transcriptomics and SURF results (Left: tissue section; Right: SURF-inferred cell components)

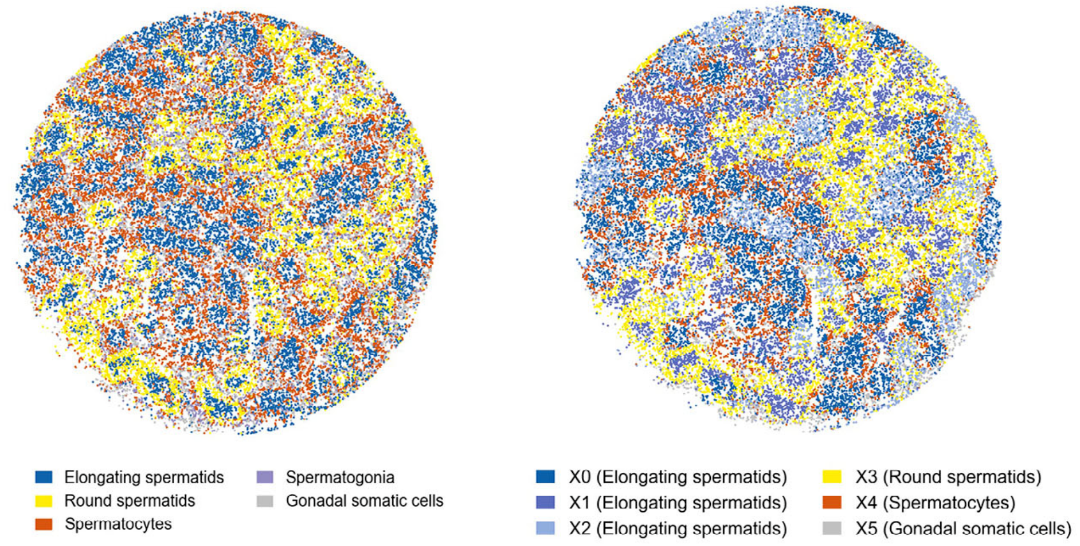

SURF was further applied to a Slide-seq dataset profiling mouse spermatogenesis. In this dataset, SURF identified six major cellular components within the seminiferous tubules.

The inferred components showed clear spatial separation corresponding to different stages of germ cell development, including the distinction between spermatocytes and round spermatids.

Figure 4. Mouse spermatogenesis analyzed by Slide-seq and SURF (Left: original annotations; Right: SURF deconvolution results)

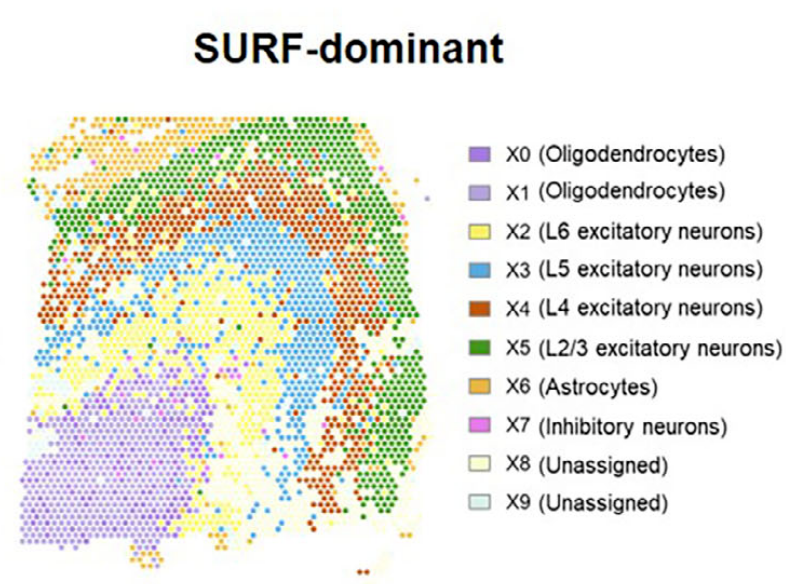

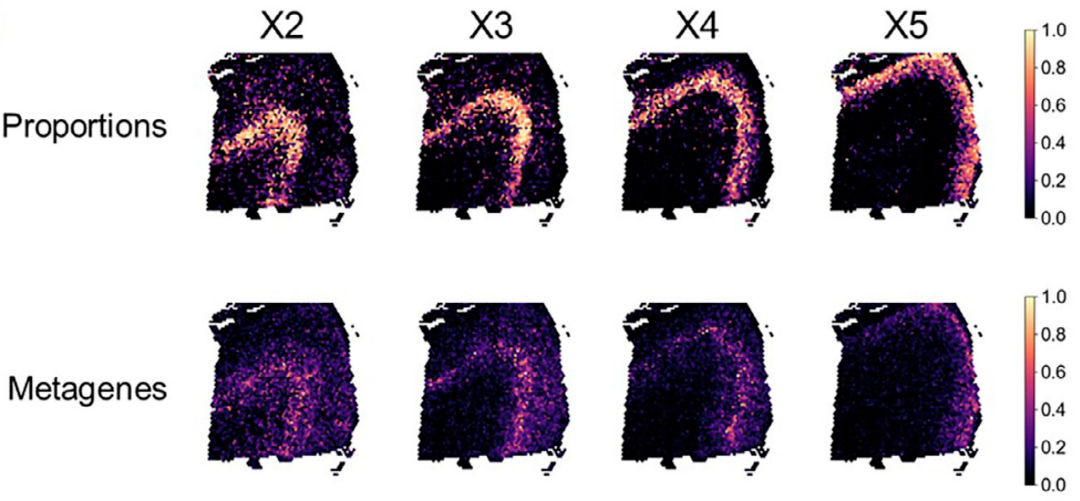

In a human prefrontal cortex dataset generated using the 10x Genomics Visium v2 platform, SURF identified ten latent cellular components. These included components corresponding to white matter cells and multiple excitatory neuronal populations spanning cortical layers L2/3 through L6.

Figure 5. Human prefrontal cortex spatial transcriptomics (Left: SURF-inferred cell proportions; Right: layer-specific gene expression patterns)

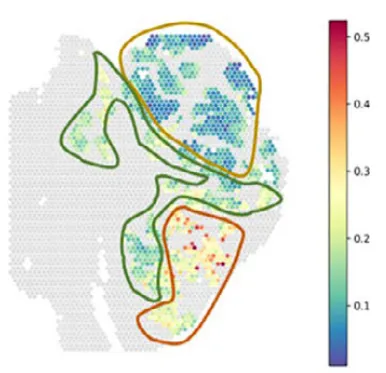

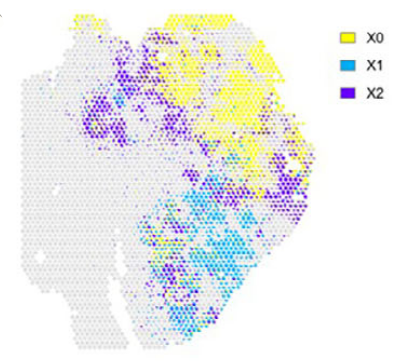

SURF was also evaluated in a disease context using a spatial transcriptomics dataset from human colorectal cancer liver metastases. In this dataset, SURF identified three malignant cellular components corresponding to epithelial, transitional, and mesenchymal-like states along the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) continuum.

Figure 6.Colorectal cancer liver metastasis spatial analysis (Left: EMT gene set scores; Right: SURF-inferred malignant cell states)

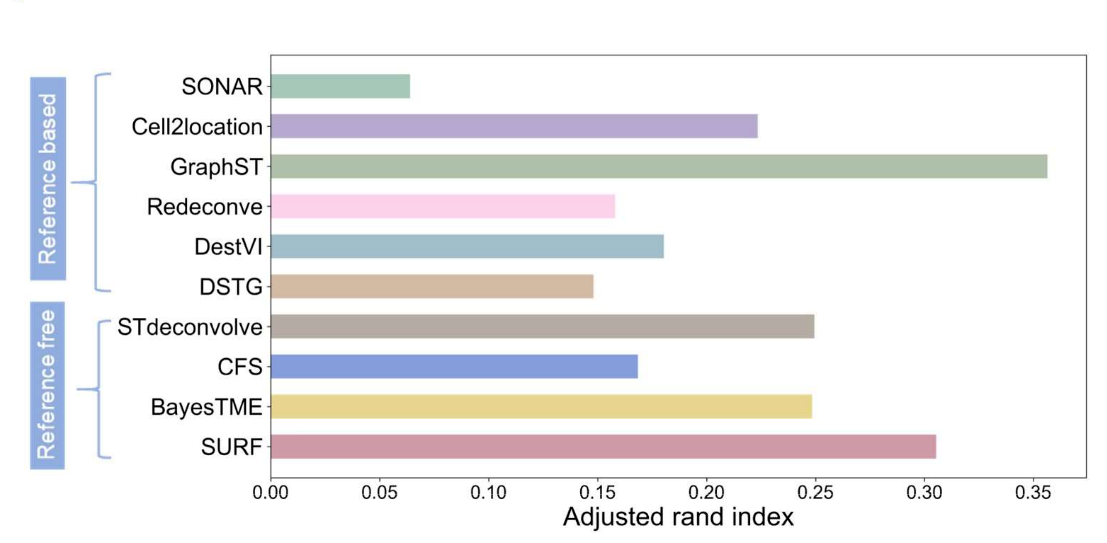

The development of SURF demonstrates that spatial transcriptomics analysis does not necessarily require a “single-cell-first” workflow. In benchmark evaluations, SURF achieved agreement with original annotations comparable to leading reference-based deconvolution methods, despite operating without single-cell reference data.

Figure 7. Benchmark comparison of spatial deconvolution methods using adjusted Rand index.

At the same time, several limitations should be considered.

First, SURF is based on a deep learning framework and typically requires GPU resources to achieve efficient training.

Second, the number of latent cellular components must be selected empirically. Testing different component numbers can improve interpretability but increases computational cost.

Third, when multiple tissue sections are analyzed, SURF is applied to each section independently, and additional steps may be required to integrate results across sections.

Finally, the latent components inferred by SURF (such as X0, X1, and X2) do not correspond to predefined biological cell types by default. Biological interpretation requires downstream annotation using marker genes, pathway analysis, and domain knowledge.

Spatial transcriptomics and single-cell sequencing projects often involve multiple experimental and analytical steps, which can be challenging to coordinate—especially when samples are limited or timelines are tight.

At Omics Empower, we provide end-to-end support covering experimental execution and downstream data analysis. This includes sample preparation, library construction, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis for both spatial and single-cell transcriptomics.

By integrating wet-lab processes with downstream analysis, we help research teams obtain high-quality data and interpretable results within a predictable and efficient timeline.

[1] Oliveira, M.F.d., Romero, J.P., Chung, M. et al. High-definition spatial transcriptomic profiling of immune cell populations in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 57, 1512–1523 .

[2] Escalante, Augusto & González-Martínez, Rocío & Herrera, Eloisa. (2020). New techniques for studying neurodevelopment. Faculty Reviews. 9. 10.12703/r/9-17.

This approach is useful when matched single-cell data are unavailable, poorly matched, or when researchers want to explore spatial organization before conducting additional single-cell sequencing experiments.

Germany: Arnold-Graffi-Haus / D85 Robert-Rössle-Straße 10 13125 Berlin

United States: (CA) 2 Goddard, Irvine, CA 92618 • (IL) 8255 Lemont Rd, #1, Darien, IL 60561

Hong Kong: Room 618, Building 6, Phase One, Hong Kong Science Park, No. 6 Science Park West Avenue, Pak Shek Kok, New Territories, Hong Kong

Germany: Arnold-Graffi-Haus / D85 Robert-Rössle-Straße 10 13125 Berlin

United States: (CA) 2 Goddard, Irvine, CA 92618 • (IL) 8255 Lemont Rd, #1, Darien, IL 60561

Hong Kong: Room 618, Building 6, Phase One, Hong Kong Science Park, No. 6 Science Park West Avenue, Pak Shek Kok, New Territories, Hong Kong